OLD SCHOOL SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith were African American men who were lynched on August 7, 1930, in Marion, Indiana, after being taken from jail and beaten by a mob. They had been arrested that night as suspects in a robbery, murder and rape case. A third African American suspect, 16-year-old James Cameron, had also been arrested and narrowly escaped being killed by the mob. The teenagers had been accused of murdering a white man and raping a white woman. The noose was removed from the neck of one of the three, James Cameron, when a woman, by one account, shouted, “Take this boy back! He had nothing to do with any raping or killing.” Mary Ball later testified that she had not been raped. According to Cameron’s 1982 memoir, the police had originally accused all three men of murder and rape. After the lynchings, and Mary Ball’s testimony, the rape charge was dropped.

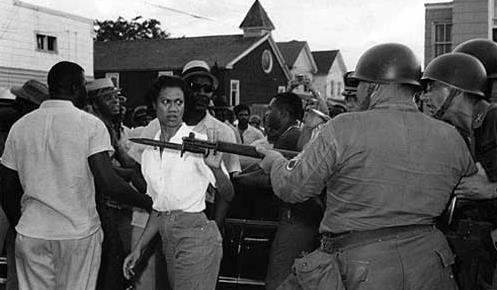

The two 1930 lynchings before thousands of whites, some of whom returned home with body parts and other souvenirs, were captured in an iconic photo. But today nothing in Marion memorializes the lynchings.”The night of the lynching, studio photographer Lawrence Beitler took a photograph of the crowd by the bodies of the men hanging from a tree. He sold thousands of copies over the next 10 days, and it has become an iconic image of a lynching.

In 1937 Abel Meeropol, a Jewish schoolteacher from New York City and the adoptive father of the sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, saw a copy of Beitler’s 1930 photograph. Meeropol later said that the photograph “haunted [him] for days” and inspired his poem “Bitter Fruit”. It was published in the New York Teacher in 1937 and later in the magazine New Masses, in both cases under the pseudonym Lewis Allan. Meeropol set his poem to music, renaming it “Strange Fruit”. He performed it at a labor meeting in Madison Square Garden. In 1939 it was performed, recorded and popularized by American singer Billie Holiday. The song reached 16th place on the charts in July 1939, and has since been recorded by numerous artists, continuing into the 21st century.

After years as a civil rights activist, in 1988 James Cameron founded and became director of America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, devoted to African-American history in the United States. He intended it as a place for education and reconciliation.

In 2007, artist David Powers supervised the creation of a mural, titled American Nocturne, in a park in downtown Elgin, Illinois. The mural depicts the bottom half of the Beitler photograph, showing the crowd at the lynching but not the bodies of Shipp and Smith. The artwork was intended as a critique of racism in American society. In 2016 there was a public controversy when the similarity between the mural and the photo was posted on social media. The mural was moved from the park to the Hemmens Cultural Center.The Elgin Cultural Arts Commission then recommended to the city council that the mural be permanently removed from public display.

Follow

Follow